This is the first blog in a three-part series on loneliness and isolation in Wales. Part two is available here, and part three is available here.

In this blog, Suzanna Nesom discusses what we know about loneliness as a concept, and what the evidence says about loneliness in Wales.

The Welsh Government has committed to publishing a Loneliness strategy, set to be launched by the end of March. This comes at a time of increased interest in loneliness across the UK, with the UK Government launching its first Loneliness Strategy; the What Works Centre for Wellbeing releasing a Tackling Loneliness evidence report; and the release of the BBC Loneliness Experiment results. These are positive first steps in tackling an issue linked to adverse health effects, including higher rates of depression, anxiety and mortality, and one consistently reported as affecting all ages.

First, it’s worth clarifying some of the concepts surrounding the topic of loneliness and isolation. Whilst related concepts, loneliness and isolation are different things and they should not be used interchangeably. Typically, loneliness is a person’s subjective feeling about the quality of relationships (how close or otherwise are a person’s relationships), whilst isolation refers to the objective quantity of these relationships (how many relationships does a person have). It means it’s possible to feel lonely even when you are in contact with many people, and be isolated even if you don’t feel lonely. However, as you would expect, people will experience loneliness and isolation slightly differently and to different extents over a lifetime.

Loneliness in Wales

Wales recognises that loneliness is a key component of well-being, so tracks “the percentage of lonely people” through the National Survey for Wales. So far, data has been collected for 2016-17 and 2017-18, with each asking over 10,000 people across Wales about their subjective experience of loneliness. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with six statements. If they identified with three or more statements associated with loneliness, then they were considered to be lonely. The results from 2017-18 suggest 16% of people surveyed were lonely, which is 1% lower than the 2016-17 data.

These statistics are lower than other national studies, which usually record an average of 25% of people being lonely (though this is often much higher for Southern European countries) and also much lower than the 33% the BBC Loneliness Experiment found for the entire UK. You might think that this means that people in Wales are less lonely than their neighbours, but because there is no agreed way of measuring loneliness, the differences may just be down to the method used.

Which Groups Are Lonely?

Of the few characteristics that were strongly associated with loneliness across both National Surveys for Wales, material deprivation and age were specifically highlighted in both the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 reports – although it’s important to remember that these show correlation rather than causation!

The Welsh Government considers a person to be materially deprived if they are not able to access a certain number of goods and services. In 2017-2018, this group appeared to be three times as likely to be lonely than those not experiencing material deprivation. This is slightly higher than the 2016-17 results, where 37% of people in material deprivation were lonely, compared to 14% of those not in material deprivation.

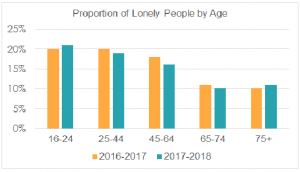

Age was also a significant factor, with those aged 65+ being less likely to be lonely than those aged 16-64 and the proportion of lonely people decreasing with age. Whilst this is somewhat surprising as older people are usually portrayed as the most vulnerable to loneliness, this pattern is reflected in the BBC Loneliness Experiment, despite loneliness being measured differently. It is important to highlight this as loneliness is an issue across the life course.

Source: National Survey for Wales

Source: National Survey for Wales

Surprisingly, Welsh Government data does not show a consistent link between where someone lives and their likelihood of being lonely. In 2016-17, the data suggested that people in urban areas were at greater risk, but in the latest survey, there was no link between loneliness and geography.

What happens next

The above discussion suggests that whilst measuring loneliness is difficult and somewhat questionable, serious progress has been made in trying to build the evidence base for loneliness in Wales. To strengthen this effort, research should continue to be collected for subsequent years, as well as value being placed on more longitudinal research.

In Part Two I discuss what these concepts and the available evidence means for potential loneliness interventions in Wales.