One of the projects that the Wales Centre for Public Policy (WCPP) currently has on the go looks at ways that governments can engage with the public about healthcare. The Welsh Government’s plan for health and social care “A Healthier Wales” sets out public engagement as a core part of its healthcare approach going forward, but the specific form that this will take is still to be finalised. We’re building on previous work on participatory budgeting by the centre’s predecessor the Public Policy Institute for Wales, along with wider research into forms of engagement in Wales and internationally, to help to establish what form the Welsh Government’s commitment to public engagement on health might best take in practice.

The Welsh Government are not alone in their interest in ways of enhancing the public’s role in policy decision-making. The Royal Society of Arts (RSA) think tank have highlighted deliberative democracy (a form of heightened public engagement in democracy) as one of their main campaign areas. They’ve also teamed up with the charity Involve, which works exclusively on the topic of improving public participation. At a recent conference on policy success and failure at the Bennet Institute for Public Policy in Cambridge, the issue of public engagement came up frequently. There is a sense that the current political situation might be propitious for greater public participation in decision-making over and above the current democratic norm; in other words, there may currently be a “window of opportunity” for this idea. This is particularly the case in Wales, which even has legislation in the form of the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act that lists involvement as a core decision-making principle for public bodies.

A spectrum of engagement

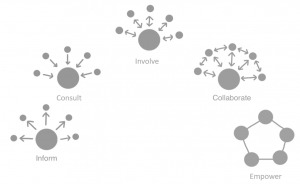

The degree and type of public engagement varies greatly depending on the context and the desired outcomes. We find the International Association of Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation (adapted in the image by Involve below) a good way into thinking about this. It charts the incremental levels of engagement starting with “informing” through “consulting,” “involving,” “collaborating” and finally “empowering”. Informing simply means keeping the public up to speed about a specific topic area, but doesn’t provide an opportunity for them to feed into decision-making. Consulting involves gathering public feedback on governments’ decisions, whilst involving and collaborating entail working with the public throughout the decision-making process. Empowering is the highest degree of public engagement and gives the public the final say in decision-making. That said, we should be wary of automatically attributing value judgements to the spectrum. Just because empowering is the highest degree of engagement doesn’t mean that it is always the most appropriate, which will depend on the specific context.

Credit: Involve

Credit: Involve

Different ways of engaging

In practice, engagement tends to take the form of a few set models. The Public Policy Institute for Wales carried out an evidence review into participatory budgeting, a form of engagement in which local populations are involved in decisions about how public funds are distributed. The evidence review provides a framework for deciding which form of participatory budgeting is appropriate for the context, based around a series of questions: What is the aim? What should the degree of participation be? What is the scale of the process? Who will be involved in the process? At what stage will people be involved? What is the method of involvement? Although these questions stem from the participatory budgeting work, they’re relevant to public engagement in general, and we’re using them as part of early research for our current project on public engagement and health.

A popular method of engagement in the health context is the citizens’ jury. This usually involves a group of between 12 and 24 people who are chosen to represent the demographics of a certain area, and who take part in a series of discussion sessions about a specific issue over the course of several days. Evidence from experts is presented and reviewed and the jury ultimately decide amongst a range of alternative courses of action, in a similar way to a legal jury. Evidence suggests that citizens juries are an effective means of engagement, since they’re small enough to allow productive deliberation, but also diverse enough to bring together a range of perspectives.

Citizens’ assemblies are similar but on a larger scale; from around 40 to 100 participants, and often over a longer period of time. The recent referendum in the Republic of Ireland over whether to remove the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment was based on recommendations from a citizens’ assembly, and is a high profile example of the possible impact of these forms of engagement. There have also been recent citizens assemblies on social care funding in England and Ireland. Other models of engagement which are less widely used include deliberative polls and consensus conferences, but the evidence base about their effectiveness is more limited.

Our approach

With all of this in mind, we started off by reviewing the different forms of engagement already in place in Wales. In parallel, we identified references to engagement in “A Healthier Wales” and looked at the form they might take in practice both in terms of where they fit on the spectrum of engagement, and what scale of engagement would be most suitable. Building on this, we’re currently reviewing the evidence on public engagement around three outcomes stated in A Healthier Wales: how to encourage the populations to have healthier lifestyles, how to design patient centred care, and public engagement for systems’ change. These will form the basis of a series of workshops that we’ll put on later in the year where we’ll facilitate a discussion with experts, Welsh Government officials and practitioners from the health and social care system and other sectors that are involved. In these, we’ll discuss the different models of engagement that have worked elsewhere and the implications of this for engagement in health and social care in Wales.

Photo by Mikael Kristenson on Unsplash